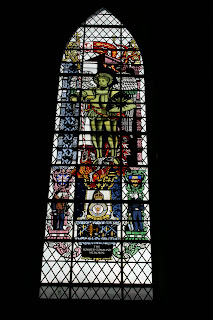

Memorial plaque to 153 Squadron, Scampton village Church.

My Dad, who died last year, spent his WWII active service as a tail gunner in RAF Bomber Command flying in Lancasters in 153 squadron. He wouldn't talk about his experiences very much except for an odd occasion until just a few months before he died when he began to talk more openly about his experiences. Mainly he would talk about an 'Operation Manna' where RAF and USAF dropped food to starving civilians in Nazi occupied Holland in April 1945, but occasionally other things would come to the fore.

Joining up in 1943 as soon as he was able due to his age, he was late into active service as a result of a combination of things; he was hospitalised when he contracted jaundice, and delayed being released into operational aircrew while recuperating from some injuries sustained when a Wellington bomber he was training in suffered engine failure and crashed in trees near the edge of the airfield on trying to land. This engine weakness was something Wellingtons were known to suffer from apparently. This meant that he only was operational for the last few months of the war. Perhaps this helped preserve him, unlike many of his counterparts.

I have been tracing his and his comrades operations from the squadron history and I thought it would be interesting to follow the story of those men over the final months of the war in as close to real time as possible. This is inspired in no small way by Mornings Minion, a fellow blogger who's tales I follow. She very effectively used letters and photographs from a relative killed in WWI to tell his very personal story in the lead up to remembrance day. While I don't have that kind of an archive I feel that I would still like to try and piece together what I can of the experience of those young men, ordinary and extraordinary, at a critical time of their lives and our history, in an age very different to our modern, multi-media and ultra connected time. I think that this may take the shape of an operational report with some added excerpts taken from a couple of books in my library, books which I bought after dad died to try and help make sense of some of the information he told me about things he was proud of and things that had scared him at the time.

First though some background on the Squadron and the organisation of bombing raids during the latter part of WWII. Then by way of introduction to the calendar approach I hope to take to the operations phase I will run through the experience of the Squadron from October '44 to the start of Jan '45 as I have found out so far.

During the second World War , Royal Air Force Bomber Command eventually comprised of seven groups in the United Kingdom, strategically stationed near the east coast of England, broadly based as follows:

No 1 Group North Lincolnshire 14 Squadrons

No 3 Group East Anglia 11 Squadrons

No 4 Group South Yorkshire 10 Squadrons

No 5 Group South Lincolnshire 13 Squadrons

No 6 Group North Yorkshire 13 Squadrons (all RCAF)

No 8 Group Cambridgeshire 12 Squadrons

No 100 Group Norfolk 6 Squadrons

No 8 Group, formed in 1942, comprised of the 'Pathfinder Force' to provide specialist marking of targets. Also the 'Master Bombers' who positioned themselves over the target area to control attacks as they developed.

No 100 Group was formed in November 1943 to provide electronic and radio counter-measures designed to foil and mislead enemy radar and other defensive facilities.

153 SQUADRON BADGE

153 Squadron had a pedigree dating back to WW1 but disbanded at the end of the war. It was re-formed as a night fighter squadron on the 14th October 1941 from a flight of 256 (N/F) Squadron stationed at Squires Gate. It moved to Ballyhalbert in Northern Ireland, being equipped with the ill-starred Boulton Paul 'Defiant'. During 1942 it was re-equipped with Beaufighters and in December 1942 moved to Algeria where it operated in a night-fighter role. As the war in the Mediterranean moved northwards, the Squadron re-located in July 1944 to Sardinia, to provide intruder missions over Northern Italy and to assist allied forces landings in Southern France. No sooner was this fully accomplished, than the Squadron disbanded on 5th September 1944.

The Squadron re-formed as a heavy bomber squadron at Kirmington {now Humberside airport} on 7th October 1944, being equipped with Lancasters, but after less than a year, was again disbanded on 28th September 1945.

On 15th October 1944, 153 Squadron moved to Scampton in Lincolnshire.

RAF SCAMPTON

Thanks to the epic raids against the German dams by No 617 Squadron flown from Scampton, the name of the airfield became very widely known to the British nation generally. What is less appreciated is that the "Dambusters" took off on grass runways; in fact, shortly after their historic attacks, the airfield was closed for eighteen months whilst concrete runways were laid. When 153 Squadron flew in to occupy the base they became the first to enjoy the improved facillities.

Three runways were created, bearing (in degrees) 10/190, 50/230 and 110/290. The former ran almost parallel to the Roman Ermine Street,(the A15) which passes the base. The latter was the shortest and most disliked by pilots who had to keep a watchfull eye on high-sided vehicles using the A15 because just beyond the boundary hedge their paths crossed almost at right-angles. However, most used was the main runway (50/230) which afforded crews a superb view of Lincoln Cathedral when flying south as they usually did while on ops. The cathedral had a huge emotional hold over Dad who said he always felt safe when he saw it. It now holds the bomber command memorial.

Being a permanent, peacetime station, Scampton provided accomodation and amenities that no war-time aerodrome could rival. There were few, if any, regrets at a move which removed the neccessity of sloshing across open, wind-swept spaces to wash or use the unheated, bare concrete-floored latrines; and dispensed with the need to use bicycles to circulate between widely dispersed Nissan huts variously got up to act as eating, sleeping, working or entertainment centres as at Kirmington. 153 Squadron was indeed fortunate in being able to move before Winter arrived.

SCAMPTON - NOVEMBER 1944

By the end of October the squadron could muster 36 crews. During November, a further 7 crews arrived, but with postings and losses, the total active strength at 30th Nov was 37. Although the squadron's authorised aircraft strength was 24, only in theory could this number ever be simultaneously airborne, since machines had to be taken out of service at regular intervals for periodic maintenance and overhauls, whilst some required repairs to make good operational damage: also loss replacements had to be effected. In fact, the maximum effort ever achieved was on 27th November, when from an available total of 22 aircraft, 20 were despatched to Freiburg - a figure never again reached throughout the squadron's existence.

Under the aircrew leave rotation system (six weeks on duty - the seventh week on leave), 5 or 6 crews would be away on leave at any given time. After making provision for some sickness, there was therefore not all that much spare capacity within the authorised establishment. It is interesting to note that of the 160 sorties mounted in November, well over half (108) were flown by only 18 of the crews. Its difficult to imagine the stress of such sustained operations on such relatively few men.

Each day (the timing depended on whether operations had been flown the previous night), crews would attend a flight muster parade; captains to the fore. The Flight Commander would ask each captain whether his crew was operational or not. If the pilot, navigator or the bomb aimer were sick (which generally meant suffering colds or ear trouble, either of which could spell real danger in the non-pressurised conditions at higher altitudes) the crew would be grounded. Other crew members unfit to fly, could - and would - be replaced or interchanged. If the crew was reported as being O.K (and an operation was planned) the captain was warned that they were regarded as being on 'stand by'.

STAND BY

November saw 10 days of 'stand down' (when personnel not on duty could pursue their own interests): 10 days when operational attacks were flown, and 10 days in the state of suspended animation known as 'stand by'. The first two categories are self-evident: for the uninitiated 'stand by' requires a more detailed explanation.

The daily activity on any operational heavy bomber station like Scampton was dictated by the choice of targets selected by HQ Bomber Command, which itself had to observe one of the basic principles of flight, i.e. that every aircraft has a maximum lifting capacity, beyond which it simply cannot get airborne. Titled the 'all up weight', it comprises fixed and variable elements. Foremost of the fixed elements is the aircraft itself - plus its equipment, guns, ammunition and the crew. The variable elements are fuel and bomb load. The further the target, the more fuel (weighing 10 lbs a gallon) is required - which proportionately restricts the weight of bombs that can be carried.

To bring a squadron to readiness, HQ Bomber Command would initially issue a 'stand by' order. Such an order (invariably classified 'Secret') would detail the number of aircraft to be made ready, together with the fuel gallonage and the various types (and numbers) of bombs to be loaded. Ground crew fitters and riggers, together with instrument mechanics and other specialist tradesmen, would ensure that all was readied for test flights to be made by the aircrews on 'stand by'; once they pronounced themselves happy with the state of their aircraft, then the armourers and petrol bowser operators could get on with loading duties. However, having carried out this strenuous preparatory work it was not unusual for the orders to be changed, requiring topping-up or draining of fuel tanks and de/bombing and re/bombing of the aircraft. On many occasions this work had to be done at night, in all kinds of wind and weather. It did not help if the operation was then cancelled (which was not at all uncommon)

Similar repercussions would arise when the original timing of an attack was changed. In addition to the ground crews out on the exposed dispersal sites, the mess staff, the motor transport drivers and RAF Service Police had to accept alterations to their detailed plans, so as to meet the revised timetables. Its worthwhile mentioning one of the least approved duties which fell to the mess orderlies in their role of 'wakers-up' of aircrew due to fly on operations, for on them fell the unfortunate task of having to do the rounds even when operations were cancelled. In theory, this was to avoid the panic which might ensue if someone woke up late thinking he had missed his date with destiny - but it took a special sense of humour to appreciate being woken up in the middle of the night, just to be told there was in fact no need to wake up!.

To be fair to Bomber Command HQ, the disruption created from changing 'stand by' instructions could often not be avoided. Deteriorating weather conditions, affecting take-off or landing prospects had to be allowed for. Close support bombing attacks, designed to aid army advances, could be negated by ground forces occupying the target area faster than expected.

It was often the case that crews reached the Briefing Room - and sometimes their aircraft - before cancellation was ordered. On one such occasion, when a pilot was late leaving a briefing, word came through that the operation was cancelled. Showing great initiative, he dashed to the Parachute Room and ensured he drew his flying rations (chocolate bar, chewing gum and barley sugar) - actively helping with the issue to other crews, before news of the cancellation reached that area. He knew that once issued, such rations were never taken back! This action got him into trouble with the Squadron Commander, who nailed him, but he got out of that situation by asking, "What would you have done in the same circumstances?" Exit one Wing Co, laughing.

OPERATIONS

Dads crew 1944/5, Dad front row right.

On 2nd November, 18 aircraft were despatched to Dusseldorf, four of them manned by crews on their first 'op'. It proved to be a rough evening. NE 113(P4-H) had to abandon the flight, due to complete loss of power in the starboard outer engine; PB 515(P4-N) came under a sustained attack from a Ju88; sadly, F/O Bob McCormack flying PB 639(P4-I) on his first solo operation, was shot down together with his four fellow Canadians and two RAFVR crew. There were no survivors. The raid itself was deemed successful, despite heavy A/A fire and intense fighter activity, which harassed the stream right back to the French coast.

On 4th November, 17 aircraft were sent to attack a synthetic oil plant at Bochum. Pilot of NG 189(P4-P) found his supercharger unserviceable and had no option but to jettison his bombs and to abort; PD 380(P4-X) lost the use of the blind-flying panel and also aborted; One crew suffered severe damage when attacked by an ME 262 (this was the first reported attack by the newly introduced German jet-propelled aircraft) and although the crew emerged unscathed, the damage to the aircraft took over three weeks to repair. The actual raid was concentrated and all crews considered it successful. Enemy fighters were highly active.

Over the rest of the month, both by day and night, a further five raids were made against synthetic oil plants at Wanne Eickel, Dortmund and Gelsenkirchen - all within or close to the "Happy Valley" of the Ruhr. On the last of these, Fl/Lt Bill Pow flying PD 380(P4-X) on his first solo operation was killed, together with his RAFVR W/Op and Flight Engineer and their four Canadian comrades. (Both Pow and his W/Op, Warrant Officer Ray Jones, had relinquished their training instructor posts to fly operationaly). Five other aircraft suffered varying degrees of flak damage. Due to poor weather and considerable cloud cover over target areas, much of the bombing had to be made on skymarkers {flares dropped by master bomber at target location. This had the effect of lighting the clouds but made aircraft highly visible to anti-aircraft defences} and the resultant damage did not reflect the effort involved.

On 16th November, 13 aircraft took part in a daylight attack in support of the American army's advance against the small town of Duren - which lies mid-way between Aachen and the Rhine. It was only a short way over the 'bomb line' which denoted where the leading army elements were, and definite identification of the target was essential to prevent allied losses from 'friendly fire'. In the event, an almost copybook concentrated attack developed, which obliterated the target. In response to a substantial escort of Spitfires and Mustangs, enemy resistance was limited to moderate flak - but that was sufficient to create problems for PA 168(P4-G) which, owing to malfunction of its D/R compass, arrived late over the target. No sooner had F/Sgt John Hows dropped his 'cookie' {4000lb bomb} than there was an almighty bang; in addition, a strong smell of cordite and the aircraft began to 'wander'. Although all four engines were still running, many of the controls were not responding normally, and all hydraulic power appeared to be ineffective. The bomb doors could not be closed, and on checking the open bomb bay, Hows was horrified to see smoke coming from the incendiaries, which were still aboard - so he released the lot, canisters included. All of the crew responded on the intercom, so F/O Les Taylor decided to fly by using engine power to compensate for lack of trim and normal rudder control. A 'Mayday' call got them directed to the emergency landing strip at Woodbridge, which, following a very difficult flight, they found shrouded in poor visibility. His entailed landing using 'FIDO' - the system whereby the runway was outlined by parallel troughs of burning paraffin, which caused the ground mist to lift sufficiently to allow aircraft to land. This was a hazardous undertaking at the best of times, and not one to be lightly undertaken in a badly weakened aircraft. But the landing was safe - if somewhat bumpy - and met the old airforce criteria - "if you can walk away from it, it's a good landing". The following morning the crew returned to Lincoln by train. 'G' remained at Woodbridge, undergoing repairs, until mid-January 1945.

The weather conditions on the 18th November grew steadily worse as the raid on Wanne Eickel was being flown, to the extent that all 18 aircraft were ordered to divert to South Norfolk; 15 did so and were entranced to find they were on USAAF bases at Horham and Mendlesham Heath. Although their overnight accommodation proved both sparse and cold, the warmth of their reception by the American Army Air Force more than compensated for the inconvenience suffered. Regaled with generous portions of bacon and eggs, followed by tinned fruit and other half-forgotten luxuries, the crews were able to visit the P/X store (the American equivalent of the NAAFI) were they could purchase unlimited quantities of many rationed goodies, such as sweets, cigarettes, soap, chocolate and even cigars. Before the Lancasters returned to base, the Yankee airmen wanted to see inside the bomb-bays, which could contain more than double their own payload. They were duly obliged. But pride goes before a fall! Fl/Lt Peter Baxter (Eng Ldr who was flying in PB 642(P4-W) because their regular F/E was sick) found that the bomb doors could not be closed without the crew's manual assistance, which provoked ironic jeers from the USAF.

Three aircraft failed to receive the diversion signal and overcame atrocious weather conditions to land at Scampton. They each received a reprimand for their failure to carry out orders, but they were hurt much more when they learned of the 'rewards' the others had enjoyed!

Operations were also flown against the marshalling yards at Freiburg and Aschaffenburg; neither particularly successful. In the case of the latter, neither the Master Bomber nor his Deputy was able to visibly identify the Aiming Point, so crews were ordered to bomb on estimated time of arrival (ETA) or navigational aids. At Freiburg, little damage was inflicted on the railway, but the medieval township nestling in the Black Forest was practically wiped out. When leaving Aschaffenburg, NG 189(P4-P) came under frequent attacks by fighters, necessitating violent evasive action. With his fuel tanks almost empty, the pilot, F/O Sinnema (the Squadrons own 'Flying Dutchman') landing at the Carnaby emergency landing strip to re-fuel.

One most unusual event occurred prior to take-off at noon on 29th November. Whilst taxiing round the perimeter track, the Verey pistol was inadvertently discharged inside NG 185(P4-A), filling the cockpit and the front end of the aircraft with dense smoke. Suspecting a fire, pilot Fl/Lt Holland cut the engines and, after giving the order to abandon the aircraft, used his overhead escape hatch to abandon the plane. Sadly, he slipped off the wing and so badly injured his back that he had to be invalided out of the service. Following behind in ME 182(P4-F), F/Eng Frank Etherington saw the smoke and flame, and assisted his pilot F/O Art LaFlamme to beat a hasty retreat in case P4-A should explode. Meantime, the 'fire' was successfully extinguished by the navigator and bomb aimer, both of whom were too busily occupied to register their captain`s order to abandon the aircraft. The nominated reserve crew led by P/O Schopp, then took over the airplane, and flew it on the raid without further problems.

SCAMPTON - DECEMBER 1944

The number of crews on squadron strength reduced during the month from 37 to 33. The welcome news was that no fewer than 5 crews completed their tour of 30 operations.

CHANGING WAYS

Significant changes to the pattern of the air war in Europe began to emerge. The thrust of the allied armies had lost momentum on reaching the German border, but the liberation of France, and large areas of Belgium and southern Holland, enabled allied fighter aircraft to move into airfields close to the front lines, resulting in more fighter escorts being given to allied bomber forces. Opportunity was taken to set up advance Gee stations, which greatly improved the range and clarity of their signals; the counter-measures of 100 Group (particularly the Mandrel screen radar jamming system) were greatly enhanced. The German air defences (fighter bases, early warning radar stations, ground controllers, flak batteries, searchlight detachments etc) all had to withdraw into the Fatherland. Taken together, these various factors enabled Bomber Command to change its tactics. In effect, it became possible to attack targets in the very heavily defended Ruhr valley {sarcastically named by crews as 'happy valley'}on a 'quick in-and-out' basis, by routing the main force through southern England and, swinging east over France, to get very close to the front line before emerging from behind the protective Mandrel screen for a short dash to the target. {note any operational mission aborted before leaving the area protected by mandrel was deemed not to count towards completing a tour of operation} It also provided a number of airfields in Europe on which crippled aircraft could make emergency landings, rather than taking the risk of a hazardous sea crossing.

SATURATION BOMBING.

Unappreciated by the general public, immense tactical changes had been introduced regarding the conduct of bombing raids. In order to saturate enemy defences overwhelmingly, it had became customary to concentrate the maximum number of aircraft bombing the target in the shortest possible time.To achive this,every crew was allotted an individual 'drop time' ( with a tolerance of 15 seconds early or late) - outside this time limit they were occupying someone else`s 'drop space' and incurring a real risk of collision. In the same manner, each crew was allotted a bombing height. If not in the top (highest) band they stood a very real chance of being hit by a load dropped by a higher colleague (as happened to one of the Squadron aircraft on 31st October). 453 aircraft took only 21 minutes to bomb Osnabruck whilst 497 spent 26 minutes over Mersburg. Saturation in practice!

This close proximity flying of sometimes up to 1000 aircraft Dad found very stressfull and was plagued by fear when having to take evasive action in case of collision as the pilot on word from gunners would break the aircraft into a turning 'corkscrew' dive before returning back to bombing height if possible. This was a highly dangerous maneuver in a crowded sky with aircraft above and below as well as beside. It gave dad cold sweats.

To reach the target within the very narrow time-span allotted, required a high standard of precision on the part of the Navigator and his pilot. It was customary to calculate 'backwards' from the 'drop time' to determine the times to proceed through the intermediate check points - some provided by flares put down by Pathfinder Force, others from ground features or external fixes. Following the conquests in Europe, the first turning point on this evolving journey became the town of Reading, which also became the first hazard!. Aircraft arriving there before their assessed time would overfly the town, circle round, and come in on a different bearing; those likely to arrive late would take a short cut to join the stream south of the town; meantime most arrived on schedule and set course correctly. For a time, a sharp lookout was required to avoid collisions, but eventually everyone would slot into his proper place. But it was a hazardous scenario and collisions did happen.

OPERATIONS FLOWN

On 3rd December No1 Group was ordered to attack the Urft Dam. This was a large reservoir in the Eifel region, which the Germans were using to systematically flood an area through which the Americans were trying to advance. Its destruction would create one massive flood, after which denial of free movement would no longer be possible. The squadron contributed 11 crews, all keen to emulate the exploits of 617 Squadron (the Dambusters) - also from Scampton - albeit they were carrying 14 x 1,000 lbs rather than special 'bouncing bombs'. They flew out in a 'gaggle' which has been described as a number of aircraft proceeding in roughly the same direction at vaguely the same time and approximately the same height at around the same speed - in no way to be confused with formation flying! On arrival, the Master Bomber decided that as the very small target was completely obscured by cloud, accurate bombing was impossible; he therefore issued instructions to abandon the mission - much to the disappointment of S/Ldr John Gee, who had hoped to ascertain how well the squadron would cope with such a precision task. 10 aircraft flew back to Scampton, only to find the cloud base down to 300 feet, necessitating a low level approach and landing with all bombs abroad.

The eleventh aircraft NG 189 (P4-P) flown by F/Lt Don Legg was hit by flak, which set the starboard inner ablaze; he managed to reach the sea to dump his bombs, and turned to Brussels to make an emergency landing (ironically, the aircraft was subsequently completely destroyed by a surprise German air attack on Brussels some two weeks later).

Post-war publications reveal that high level disagreements began with regard to the relative importance of strategic targets to be attacked, in particular as between oil production, communications (railway yards and canals) and centres of government/administration. This resulted in 153 Squadron flying to a mixture of targets, affected also to a large degree by severe wintry weather in the UK and over Germany. Thus, industrial targets such as the Durlacher machine tool factory (Karlsruhe), Krupps Steel (Essen), the Magirus Deutz and the Kassbohrer lorry factories (Ulm) were bombed on December 4th, 12th and 17th. The Merseburg synthetic oil plant at Leuna (close to Leipzig) which entailed a round trip of over 1,000 miles, the IG Farben chemical factories at Ludwigshafen (which included synthetic oil production), and the Scholven oil refinery (together with its storage tanks) at Gelsenkirchen, were attached on the 8th, 15th and 29th. The common factor noted in crew reports was the weather. Bad weather may have been the cause of the loss of PB 633 (P4-J), which collided with a Lancaster over Laon, resulting in the loss of the pilot F/O Harry Schopp (an American serving in the RCAF), his Canadian navigator and bombaimer and RAF flight engineer. The wireless operator and both gunners survived and were returned to the Squadron

Should a crew fail to return from operations, and no information was forthcoming that they had landed elsewhere,it became the immediate duty of the station "Effects Officer" first to list and then to impound their personal possessions, and to remove them into safe custody. Any individual who subsequently re-appeared could reclaim his possessions - otherwise, after reasonable time, they were transferred to the official RAF Effects Branch and eventually released to the man`s next of kin. The need for an Effects Officer, although prudent and necessary to aviod "affinching" or "liberation" of a missing colleague`s belongings, was inevitably likened to the approach of the grim reaper! Woe betide anyone who had loaned a missing man a book (or anything else) that did not bear evidence of his ownership. Frequent confrontations occurred, particulary in cases of shared accommodation; but once the Effects Officer impounded an item, it virtually became irrecoverable.

ARDENNES OFFENSIVE

The German army, practising rigorous wireless silence and protected by providential mists and low lying cloud, successfully assembled an army group of 1,000 tanks and supporting arms, ready for an attack on Antwerp and Brussels. On December 16th, the attack was launched, through the Ardennes, aimed at the junction of the British and American armies. They were lucky, in that England became shrouded in fog for almost a week following the onslaught, followed by very low cloud on the continent. Allied air power was rendered impotent. Conditions at Scampton were atrocious. On one or two days the fog lifted sufficiently to allow air tests, but closed down after a brief period. Crews felt frustrated at not being able to partake in army-support operations; every day, briefings were held, but to no avail. Indeed, on one occasion, crews were actually on board their aircraft when the fog came down and the operation had to be cancelled. Eventually, on 22nd December 15 aircraft took off for an attack on the rail yards at Coblenz - one of the major supply routes for the enemy.Despite persistant fog, crews took off relying on their instruments, knowing that they could not land back at Scampton. Misery was compounded when on their return to the UK.,all aircraft had to be diverted to Manston as all other airfields were once more 'fogged out'. Overnight accommodation was however at a premium, for not only had much of Bomber Command to be housed, but also the crews of U.S Fortresses and Liberators who were suffering the same fate.

The intention to attack rail supply points was bedevilled by continuing inclement weather. On the afternoon of the 23rd December, 9 of the 15 diverted squadron aircraft had managed to get back to Scampton, whilst the other six were able to land at Binbrook.. By 27th December conditions at Binbrook improved sufficiently enough to allow these 6 crews to join the attack on the rail yards at Rheydt - although Scampton was still inoperable. Ironically, on their return, all six were able to land back at Scampton.

It was perhaps fortunate for 153 Squadron that it formed when all these advantageous changes were emerging as this helped prevent excessive losses. Previously 10 of the 21 raids in October/November 1944 occurred in daylight, whilst only 1 required a night take-off and landing; the remainder evening take-offs and night landings. A similar pattern emerged in December, with 2 daylight raids and 9 evening take-offs.

In the preceding three months, the squadron had launched a total of 448 sorties for a loss of 5 crews; during January, another 5 crews were lost in flying a further 121 sorties. No obvious reason emerged to explain this steep upsurge in the rate of casualties. Only 7 targets would be attacked during the month - 3 in the first week, the other 4 spread over the succeeding 24 days. Mist, fog, drizzle and bitter wintry weather featuring sleet; snow and ice made Scampton a cold, inhospitable and dreary place, especially for ground crews. The Canadians, despite being used to very cold conditions, suffered particularly from the combination of dampness allied to the low temperatures and keen easterly winds which prevailed over Lincolnshire and severely hampered Bomber Commands ability to continue operations.

The crews took time where possible to relax and enjoy the respite. With better weather, operations would resume soon enough.

See you later

Listening to Porcupine tree 'Arriving Somewhere, Not Here.'